“For Orthodox tradition, the church is nothing more nor less than Israel in the altered circumstances of the Messiah’s death, resurrection, and the eschatological outpouring of his Spirit.” (Alexander Golitzin, “Scriptural Images of the Church: An Eastern Orthodox Reflection,” in One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic: Ecumenical Reflections on the Church, Tamara Grdzelidze, ed. Geneva: WCC Publications, 2005: 255.)

As such, Christian identity—the self-understanding of the Church—is rooted in biblical Israel; it was also shaped, especially in the early centuries, by the radical commitment to the “grafting in” of the Gentiles and by tense relations with the Israel of the Synagogue. The coexistence of Christians and Jews along two millennia, each claiming to be the Israel of God while denying this identity to the other, was marked by much pain and suffering, culminating in the tragic events of the 20th century. Too often Christians have failed to confirm their status of children of Abraham by doing the deeds of Abraham.

In the aftermath of the Shoah / Holocaust, a renewed engagement between the two traditions, and a proliferation of scholarship on Second Temple Judaism over the last half century have allowed for a better understanding of their mutual influences, and their exegetical, theological, and spiritual convergences and divergences.

Orthodox Christians in Dialogue with Jews is a project of the Orthodox Theological Society in America, which aims to gather Orthodox Christian scholars and pastoral leaders to further our understanding of our theological and liturgical tradition on the basis of these rekindled contacts, this deepened understanding of both Christian and Jewish origins, with respect for the mystery of Israel and the ongoing presence of our Jewish brothers and sisters today.

This is without doubt a large, complex, and admittedly controversial project, but it is our conviction that it is vital for the Orthodox Church, in keeping with our ever-living tradition, always to reengage our theology and practice to ensure that our teaching, preaching, and worship are grounded in the fulness of God’s truth and love.

We welcome the involvement of Orthodox Christian teachers, pastors, and theologians — whether they be scholars of Scripture, Church history, patristics, liturgy theology, or experts in Christian-Jewish relations — as well as partners and consultants from other Christian churches and Jewish tradition.

If you are interested in being involved, please complete a short, three-question expression of interest form that will enable OCDJ’s steering committee members to organise the working group’s activities. Please get in touch if you have any questions or feedback, or if you can recommend other working group participants.

Thank you for your support for this project.

The relationship between Christianity and Judaism is central to the identity of Christians and the Church. Yet for much of the past two millennia, the story of Christians and Jews has been difficult and troubled, culminating in the tragic events of the 20th century.

In the aftermath of the Shoah (Holocaust), there has been a renewed engagement between the two traditions, and, with a proliferation of scholarship and deepening of knowledge of Second Temple Judaism over the last half century, a joint effort has been made by Christians and Jews to correct historical inaccuracies and prejudices and amend theological traditions that had separated Jesus and early Christians from their Jewish contexts and driven a hard wedge between Covenant communities sharing faith in the one God of Israel.

Orthodox Christians in Dialogue with Jews, a project of the Orthodox Theological Society in America, aims to gather Orthodox Christian scholars and pastoral leaders together to study, reflect on, and renew Orthodox Christian theological and liturgical tradition on the basis of these rekindled contacts, this deepened understanding of both Christian and Jewish origins, with respect for the mystery of Israel and the ongoing presence of our Jewish brothers and sisters today.

We seek to truly know the Jewish environment in which Jesus lived and transmitted to the Church. Based on this knowledge, we will revisit critically our notion of the Church as the “the true Israel” and its relationship to other covenant people. The Church Fathers, who sought to situate the church in relation to “Israel according to the flesh,” often expressed the newness of the gospel by discrediting or belittling Jews who sought to preserve the Covenant with Moses. We are committed to the work of rereading the writings of the Fathers, with a respectful look at the people of the first Covenant, given that “the gifts and the calling of God are irrevocable” (Romans 11:29).

Without abandoning the reading of the Old Testament in the light of the resurrected Christ, we seek to deepen the perception of the New Testament in the light of the Old, studied first for itself, in order to give access to the message of Jesus Christ, true God and true man, incarnated among the Jewish people and all its tradition. This will allow us to highlight the exegetical reciprocity in the one covenant of God, and to experience the extent to which these two approaches complement and inform each other.

We also want to highlight how the separation between Church and Synagogue gradually took place in the texts of the Rabbis and the Fathers of the Church, by showing mutual influences, convergences and divergences, and by comparing the interpretations that took place in the Church and in the Synagogue. The challenge of this work is to underline the fruitfulness of an encounter between these two traditions, presenting them together while respecting areas of difference.

Adapted in part from the charter of Chrétiens orthodoxes en dialogue avec les juifs.

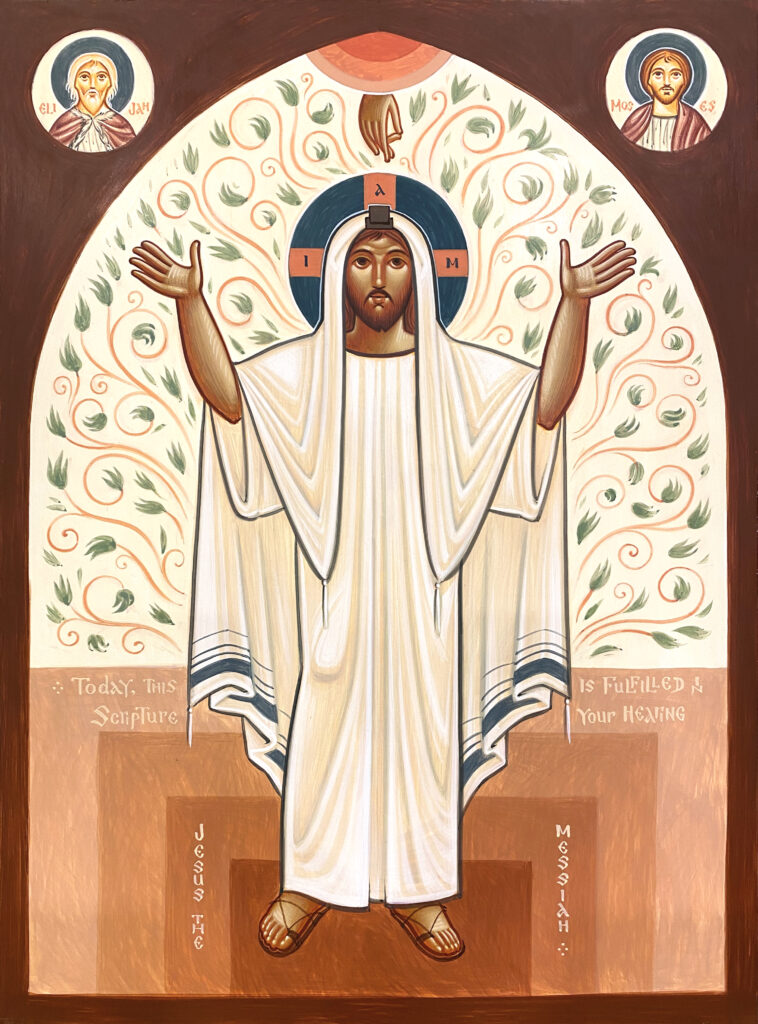

Icon of Jesus the Messiah by Kirollos Kilada

Orthodox Christians in Dialogue with Jews is a project and working group of the Orthodox Theological Society in America (OTSA).

For more information please contact info@ocdj.net

Header image: Marc Chagall’s Peace Window at the United Nations

Sign up for the monthly newsletter of the Orthodox Theological Society in America.

To receive regular updates from Orthodox Christians in Dialogue with Jews, please complete the expression of interest form.